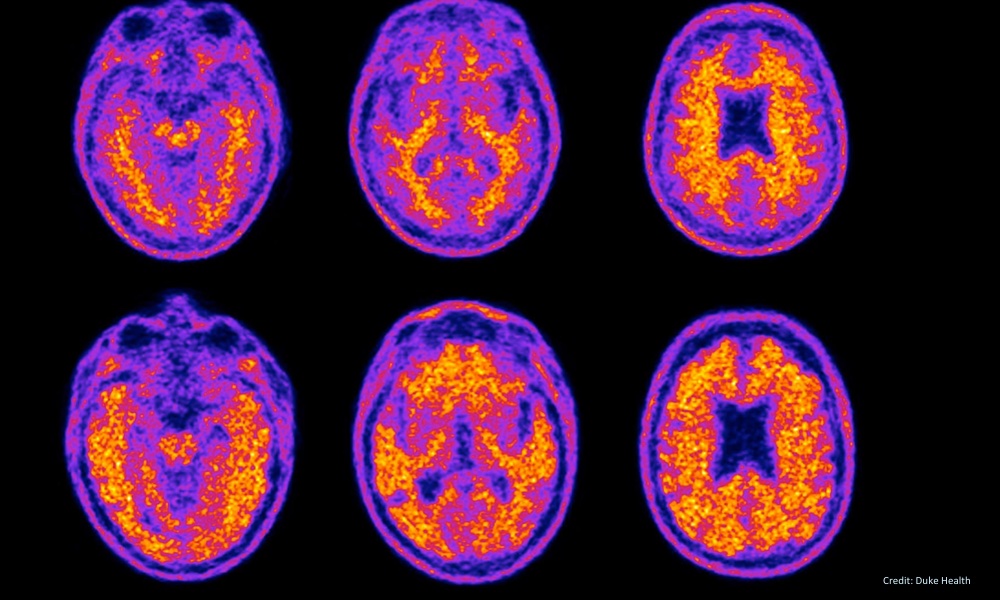

One of the most promising new therapies to help people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease involves the use of monoclonal antibodies. The treatment works by removing amyloid-B plaques in the brain. These plaques clump together between the nerve cells (neurons) in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s.

With more than 6.7 million Americans dealing with this disease, it’s not surprising there’s been a media blitz surrounding the encouraging new therapy, but with this buzz comes a barrage of confusing information.

To get a better handle on the facts about monoclonal antibodies, experts with the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) have summarized the evidence we have so far on this therapy and published an Emerging Issues article in the journal, Neurology.Not everyone who fits the criteria can take the therapy. There are risks for particular populations.

It’s important to note that their summary of the new monoclonal antibodies treatment is not a clinical practice guideline. Which means that although the information is thorough, it is not a formal document of recommendations on how to diagnose or how to treat the medical condition.

But the article is still beneficial. “Recent data on lecanaemab and other monoclonal antibody infusions targeting amyloid-B protein make clear that new agents are highly likely to be part of the toolkit for neurologists caring for people with Alzheimer’s disease,” author, Vijay K. Ramanan, of the Mayo Clinic, said, in a press statement.

“While the formal evidence base is still evolving, this article was created with expert consensus until there is enough evidence on these therapies to inform evidence-based recommendations,” he added.

Lecanemab received FDA approval in July 2023. A similar drug, Aducanumab, received accelerated FDA approval two years earlier in June 2021 — although it’s currently only available to participants in a clinical trial. A third drug, Donanemab, is expected to be approved later this year.

Not everyone who fits that criteria can take the therapy. There are risks for particular populations. The authors point out that counseling is recommended for certain people considering taking Lecanemab. They include those:

- With genetic risk factors that can lead to fatal swelling and bleeding in the brain

- With a history of certain types of strokes

- Who are taking anticoagulant medications (commonly given to older adults with cardiac issues).

These drug therapies aim to remove amyloid-B plaques and slow down the march of cognitive decline, but won’t cure Alzheimer’s. What’s more, the authors say that even when there is a reduction in the rate of cognitive decline over an 18-month period as noted in some studies, it doesn’t mean that the result will actually be experienced by the patients receiving the therapy.The goal is to help neurologists, as well as patients and caregivers, make informed decisions about the best course of treatment for early stage Alzheimer’s disease.

- the high cost of these medications

- additional patient costs that come with required diagnostic testing, administration and monitoring

- the need for multiple brain scans

- a shortage of neurologists and other medical professionals needed to provide this kind of care and meet the anticipated demand

Black and Hispanic patients have been under-represented among the study participants, who have been predominantly white. The Emerging Issues article recommends that steps be taken to include a more diverse range of study participants, particularly since the incidence of dementia has been shown to be higher among these populations.

While the outlook using anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies is promising, there’s still work to be done. As Ramanan put it, “Additional research is needed to further determine who may be most likely to benefit from these therapies, as well as to find ways to improve outcomes for people using them and enable future advances in this new era of Alzheimer’s disease care.”