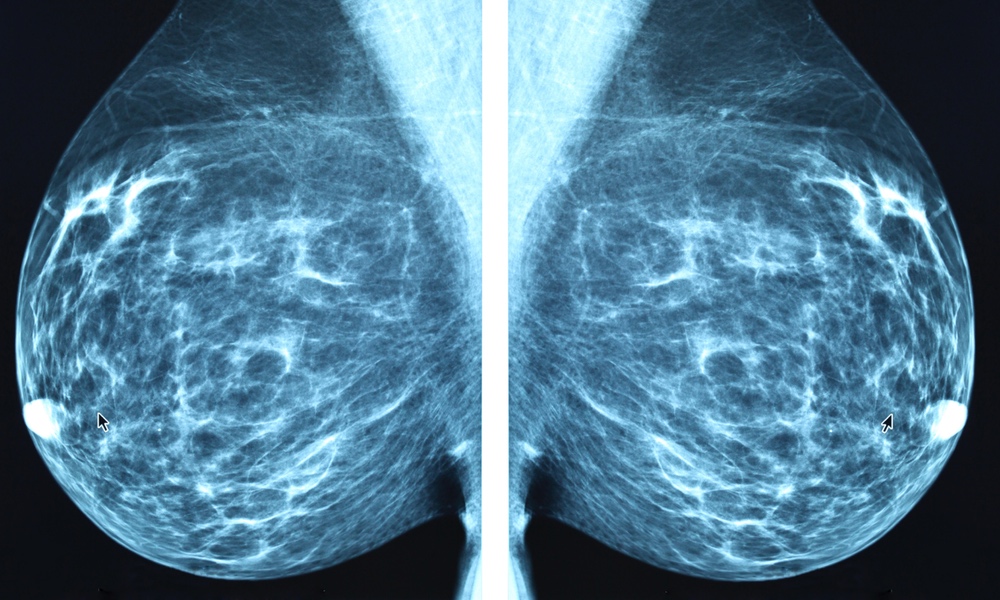

At some point all women are faced with an important health decision: when to start screening for breast cancer. In April of this year, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) revised its guidelines to recommend that women get regular mammograms every two years once they reach their 40s.

Some women, however, may not want to begin screening that early.

A team led by researchers at the University of Colorado surveyed a nationally representative sample of women between the ages of 39 and 49. The women were asked about their screening preferences before and after they reviewed a decision aid which discussed the benefits and risks of starting regular mammograms at age 40.

Before viewing the decision aid, 67 percent of the women in the study said they wanted to begin screening at their current age. That dropped to 57 percent after they reviewed the decision aid.Women who wanted to wait to screen until they were older were interested in maximizing the benefit of mammography and minimizing the harm.

Similarly, 27 percent of participants had said they preferred to delay mammograms until their 50s prior to reviewing the decision aid. After they reviewed the decision aid, 38.5 percent said they would delay screening.

Women who wanted to delay mammography were at a slightly lower breast cancer risk on average. They also said their personal risk for developing breast cancer, in the absence of family history, was an important reason they wanted to delay screening.

“Women at lower risk would not have a greater benefit or likelihood of greater benefit from screening,” Laura Scherer, lead author on the study, told TheDoctor. Women who wanted to wait to screen until they were older were interested in maximizing the benefit of mammography and minimizing the harm.

Women in their 40s are less likely to benefit from screening than women in their 50s, said Scherer, an associate professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. They are also more likely to receive a false positive diagnosis that turns out to be benign.

The proportion of women who said they would never want to get mammograms did not change, even after they reviewed the decision aid, which surprised the researchers. “Providing information about mammograms did not deter women from screening altogether, it just made some women want to screen a little later,” Scherer said.

The almost 500 women surveyed had no history of breast cancer and were not known to have the BRAC1/2 gene mutation. The decision aid also provided information about the risk of overdiagnosis of slow-growing, asymptomatic cancers that would not cause harm in a woman's lifetime.

Some of the information offered in the decision aid was surprising to many of the women. Almost 38 percent of women said they were surprised by the information about overdiagnosis; 27 percent were surprised by the information about false positives; and 23 percent were surprised by the information about the benefits of screening.

Prior to the latest update, the USPSTF guidelines had recommended that the decision to start getting regular mammograms should be made jointly by a woman and her doctor. Because this study was done prior to that update, Scherer and her team think it is important to find out if screening preferences have changed because of the new recommendation.

The study and a related editorial are published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.